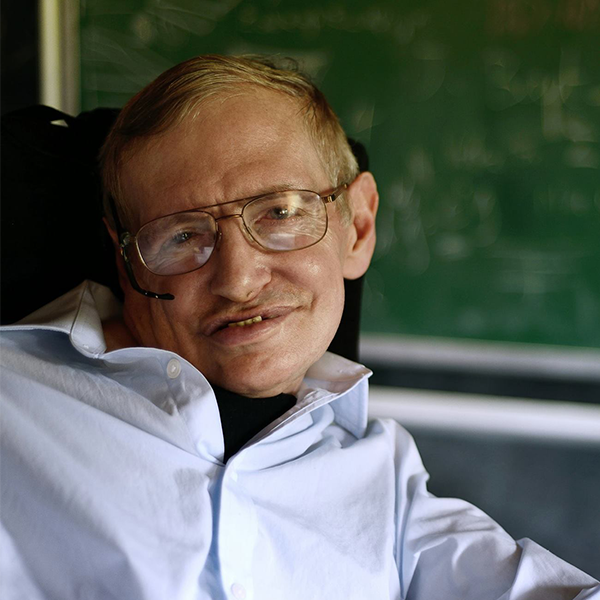

Stephen Hawking Early Life, Age, Family, Facts, Wiki, Career, Disability, Death, Personal Views, Science, Philosophy, Religion, Awards, honours, Publications, Biography

- NAME

- Stephen Hawking

- OCCUPATION

- Scientist, Physicist

- BIRTH DATE

- January 8, 1942

- DEATH DATE

- March 14, 2018

- DID YOU KNOW?

- As an author, Stephen Hawking was best known for his best seller 'A Brief History of Time.'

- DID YOU KNOW?

- At the age of 21, Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease).

- EDUCATION

- University of Cambridge, California Institute of Technology, Oxford University, Gonville & Caius College

- PLACE OF BIRTH

- Oxford, England, United Kingdom

- Family

- A Brief History of Time (1988)

- Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays (1993)

- The Universe in a Nutshell (2001)

- On the Shoulders of Giants (2002)

- God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History (2005)

- The Dreams That Stuff Is Made of: The Most Astounding Papers of Quantum Physics and How They Shook the Scientific World (2011)

- My Brief History (2013)

- The Nature of Space and Time (with Roger Penrose) (1996)

- The Large, the Small and the Human Mind (with Roger Penrose, Abner Shimony and Nancy Cartwright) (1997)

- The Future of Spacetime (with Kip Thorne, Igor Novikov, Timothy Ferris and introduction by Alan Lightman, Richard H. Price) (2002)

- A Briefer History of Time (with Leonard Mlodinow) (2005)

- The Grand Design (with Leonard Mlodinow) (2010)

- Black Holes & Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy (Kip Thorne, and introduction by Frederick Seitz) (1994)

- George's Secret Key to the Universe (2007)

- George's Cosmic Treasure Hunt (2009)

- George and the Big Bang (2011)

- George and the Unbreakable Code (2014)

- George and the Blue Moon (2016)

- A Brief History of Time (1992)

- Stephen Hawking's Universe (1997)

- Hawking – BBC television film (2004) starring Benedict Cumberbatch

- Horizon: The Hawking Paradox (2005)

- Masters of Science Fiction (2007)

- Stephen Hawking and the Theory of Everything (2007)

- Stephen Hawking: Master of the Universe (2008)

- Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking (2010)

- Brave New World with Stephen Hawking (2011)

- Stephen Hawking's Grand Design (2012)

- The Big Bang Theory (2012, 2014–2015, 2017)

- Stephen Hawking: A Brief History of Mine (2013)

- The Theory of Everything – Feature film (2014) starring Eddie Redmayne

- Genius by Stephen Hawking (2016)

Hawking was born on 8 January 1942 in Oxford to Frank (1905–1986) and Isobel Eileen Hawking (née Walker; 1915–2013). Hawking's mother was born into a family of doctors in Glasgow, Scotland. His wealthy paternal great-grandfather, from Yorkshire, had over-extended himself buying farm land and then going bankrupt in the great agricultural depression during the early 20th century. His paternal great-grandmother saved the family from financial ruin by opening a school in their home. Despite their families' financial constraints, both parents attended the University of Oxford, where Frank read medicine and Isobel read Philosophy, Politics and Economics.[27] Isobel worked as a secretary for a medical research institute, and Frank was a medical researcher. Hawking had two younger sisters, Philippa and Mary, and an adopted brother, Edward Frank David (1955–2003).

In 1950, when Hawking's father became head of the division of parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research, the family moved to St Albans, Hertfordshire. In St Albans, the family was considered highly intelligent and somewhat eccentric; meals were often spent with each person silently reading a book. They lived a frugal existence in a large, cluttered, and poorly maintained house and travelled in a converted London taxicab. During one of Hawking's father's frequent absences working in Africa, the rest of the family spent four months in Majorca visiting his mother's friend Beryl and her husband, the poet Robert Graves.

Career

1966–1975

In his work, and in collaboration with Penrose, Hawking extended the singularity theorem concepts first explored in his doctoral thesis. This included not only the existence of singularities but also the theory that the universe might have started as a singularity. Their joint essay was the runner-up in the 1968 Gravity Research Foundation competition. In 1970 they published a proof that if the universe obeys the general theory of relativity and fits any of the models of physical cosmology developed by Alexander Friedmann, then it must have begun as a singularity. In 1969, Hawking accepted a specially created Fellowship for Distinction in Science to remain at Caius.

In 1970, Hawking postulated what became known as the second law of black hole dynamics, that the event horizon of a black hole can never get smaller. With James M. Bardeen and Brandon Carter, he proposed the four laws of black hole mechanics, drawing an analogy with thermodynamics. To Hawking's irritation, Jacob Bekenstein, a graduate student of John Wheeler, went further—and ultimately correctly—to apply thermodynamic concepts literally. In the early 1970s, Hawking's work with Carter, Werner Israel and David C. Robinson strongly supported Wheeler's no-hair theorem, one that states that no matter what the original material from which a black hole is created, it can be completely described by the properties of mass, electrical charge and rotation. His essay titled "Black Holes" won the Gravity Research FoundationAward in January 1971. Hawking's first book, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, written with George Ellis, was published in 1973.

Beginning in 1973, Hawking moved into the study of quantum gravity and quantum mechanics. His work in this area was spurred by a visit to Moscow and discussions with Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich and Alexei Starobinsky, whose work showed that according to the uncertainty principle, rotating black holes emit particles. To Hawking's annoyance, his much-checked calculations produced findings that contradicted his second law, which claimed black holes could never get smaller, and supported Bekenstein's reasoning about their entropy. His results, which Hawking presented from 1974, showed that black holes emit radiation, known today as Hawking radiation, which may continue until they exhaust their energy and evaporate. Initially, Hawking radiation was controversial. By the late 1970s and following the publication of further research, the discovery was widely accepted as a significant breakthrough in theoretical physics. Hawking was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1974, a few weeks after the announcement of Hawking radiation. At the time, he was one of the youngest scientists to become a Fellow.

Hawking was appointed to the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished visiting professorship at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1970. He worked with a friend on the faculty, Kip Thorne, and engaged him in a scientific wager about whether the X-ray source Cygnus X-1 was a black hole. The wager was an "insurance policy" against the proposition that black holes did not exist. Hawking acknowledged that he had lost the bet in 1990, a bet that was the first of several he was to make with Thorne and others. Hawking had maintained ties to Caltech, spending a month there almost every year since this first visit.

Disability outreach

Starting in the 1990s, Hawking accepted the mantle of role model for disabled people, lecturing and participating in fundraising activities. At the turn of the century, he and eleven other luminaries signed the Charter for the Third Millennium on Disability, which called on governments to prevent disability and protect the rights of the disabled. In 1999, Hawking was awarded the Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society.

In August 2012, Hawking narrated the "Enlightenment" segment of the 2012 Summer Paralympics opening ceremony in London. In 2013, the biographical documentary film Hawking, in which Hawking himself is featured, was released. In September 2013, he expressed support for the legalisation of assisted suicide for the terminally ill. In August 2014, Hawking accepted the Ice Bucket Challenge to promote ALS/MND awareness and raise contributions for research. As he had pneumonia in 2013, he was advised not to have ice poured over him, but his children volunteered to accept the challenge on his behalf.

Plans for a trip to space

In late 2006, Hawking revealed in a BBC interview that one of his greatest unfulfilled desires was to travel to space; on hearing this, Richard Branson offered a free flight into space with Virgin Galactic, which Hawking immediately accepted. Besides personal ambition, he was motivated by the desire to increase public interest in spaceflight and to show the potential of people with disabilities. On 26 April 2007, Hawking flew aboard a specially-modified Boeing 727–200 jet operated by Zero-G Corp off the coast of Florida to experience weightlessness. Fears the manoeuvres would cause him undue discomfort proved groundless, and the flight was extended to eight parabolic arcs. It was described as a successful test to see if he could withstand the g-forces involved in space flight. At the time, the date of Hawking's trip to space was projected to be as early as 2009, but commercial flights to space did not commence before his death.

- Death

Hawking died at his home in Cambridge, England, early in the morning of 14 March 2018, at the age of 76. His family stated that he "died peacefully". He was eulogised by figures in science, entertainment, politics, and other areas. The Gonville and Caius College flag flew at half-mast and a book of condolences was signed by students and visitors. A tribute was made to Hawking in the closing speech by IPCPresident Andrew Parsons at the closing ceremony of the 2018 Paralympic Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea. Hawking's final broadcast interview, about the detection of gravitational waves resulting from the collision of two neutron stars, occurred in October 2017. His final words to the world appeared posthumously, in April 2018, in the form of a Smithsonian TV Channel documentary entitled, Leaving Earth: Or How to Colonize a Planet. His final research study, entitled A smooth exit from eternal inflation?, about the origin of the universe, was published in the Journal of High Energy Physics in May 2018.

Hawking was born on the 300th anniversary of Galileo's death and died on the 139th anniversary of Einstein's birth. His private funeral took place at 2 pm on the afternoon of 31 March 2018, at Great St Mary's Church, Cambridge. Guests at the funeral included Eddie Redmayne, Felicity Jones, and Queen guitarist and astrophysicist Brian May. Following the cremation a service of thanksgiving was held at Westminster Abbey on 15 June 2018, after which his ashes were interred in the Abbey's nave, alongside the grave of Sir Isaac Newton and close to that of Charles Darwin.

During the service, readings and tributes were made by Benedict Cumberbatch, who played Hawking in a BBC drama, astronaut Tim Peake, Astronomer Royal Martin Rees, and Nobel Prize winner Kip Thorne.

Hawking's words, set to music by Greek composer Vangelis, are to be beamed into space from a European space agency satellite dish in Spain with the aim of reaching the nearest black hole, 1A 0620-00.

Inscribed on his memorial stone are the words "Here lies what was mortal of Stephen Hawking 1942 - 2018" and his most famed equation.

He directed, at least fifteen years before his death, that the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy equation be his epitaph.

Personal views

Future of humanity

In 2006, Hawking posed an open question on the Internet: "In a world that is in chaos politically, socially and environmentally, how can the human race sustain another 100 years?", later clarifying: "I don't know the answer. That is why I asked the question, to get people to think about it, and to be aware of the dangers we now face."

Hawking expressed concern that life on Earth is at risk from a sudden nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus, global warming, or other dangers humans have not yet thought of. Such a planet-wide disaster need not result in human extinction if the human race were to be able to colonise additional planets before the disaster. Hawking viewed spaceflight and the colonisation of space as necessary for the future of humanity.

Hawking stated that, given the vastness of the universe, aliens likely exist, but that contact with them should be avoided. He warned that aliens might pillage Earth for resources. In 2010 he said, "If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn't turn out well for the Native Americans."

Hawking warned that superintelligent artificial intelligence could be pivotal in steering humanity's fate, stating that "the potential benefits are huge... Success in creating AI would be the biggest event in human history. It might also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks."However, he argued that we should be more frightened of capitalismexacerbating economic inequality than robots.

Hawking argued that computer viruses should be considered a new form of life, and stated that "maybe it says something about human nature, that the only form of life we have created so far is purely destructive. Talk about creating life in our own image."

Science vs. philosophy

Religion and atheism

Hawking was an atheist and believed that "the universe is governed by the laws of science". He stated: "There is a fundamental difference between religion, which is based on authority, [and] science, which is based on observation and reason. Science will win because it works." In an interview published in The Guardian, Hawking regarded "the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail", and the concept of an afterlife as a "fairy story for people afraid of the dark". In 2011, narrating the first episode of the American television series Curiosity on the Discovery Channel, Hawking declared:

We are each free to believe what we want and it is my view that the simplest explanation is there is no God. No one created the universe and no one directs our fate. This leads me to a profound realisation. There is probably no heaven, and no afterlife either. We have this one life to appreciate the grand design of the universe, and for that, I am extremely grateful.

In September 2014, he joined the Starmus Festival as keynote speaker and declared himself an atheist. In an interview with El Mundo, he said:

Before we understand science, it is natural to believe that God created the universe. But now science offers a more convincing explanation. What I meant by 'we would know the mind of God' is, we would know everything that God would know, if there were a God, which there isn't. I'm an atheist.

Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication

Hawking was a member of the Advisory Board of the Starmus Festival, and had a major role in acknowledging and promoting science communication. The Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication is an annual award initiated in 2016 to honour members of the arts community for contributions that help build awareness of science. Recipients receive a medal bearing a portrait of Stephen Hawking by Alexei Leonov, and the other side represents an image of Leonov himself performing his famous space walk and the iconic "Red Special", Brian May's guitar.[citation needed]

The Starmus III Festival in 2016 was a tribute to Stephen Hawking and the book of all Starmus III lectures, "Beyond the Horizon", was also dedicated to him. The first recipients of the medals, which were awarded at the festival, were chosen by Hawking himself. They were composer Hans Zimmer, physicist Jim Al-Khalili, and the science documentary Particle Fever.

Black Hole discovery dedication

Publications

Popular books

Co-authored

Forewords

Children's fiction

Co-written with his daughter Lucy.

Films and series

Stephen Hawking Early Life, Age, Family, Facts, Wiki, Career, Disability, Death, Personal Views, Science, Philosophy, Religion, Awards, honours, Publications, Biography

Reviewed by bd

on

August 26, 2018

Rating:

Reviewed by bd

on

August 26, 2018

Rating:

Reviewed by bd

on

August 26, 2018

Rating:

Reviewed by bd

on

August 26, 2018

Rating:

No comments: